Changing Our Lens to Better Understand Behavior

All behavior is viewed through a judgmental lens. This lens is influenced by several things:

- Our past experience – how our parents disciplined us, how we parent our own children, the culture/environment we were raised in

- Our beliefs – Do we believe that children should act and react in a certain way?

- Our knowledge and understanding – of neurological differences, sensory needs, how information is processed, language difficulties. Reading about lived experience and viewpoints can strengthen this knowledge.

- Our emotions – How does seeing and experiencing certain behavior make us feel?

- Our reactions – Do some behaviors upset or bother us more than others?

The behavior we observe is like the tip of an iceberg; below the surface of the waterline lies the cause of behavior. Delve below the waterline and understand the cause; don’t just focus on the behavior itself. This will require a shift in thinking and looking much deeper than just:

- labelling the behavior in simple terms such as attention seeking

- using rewards and punishment to get compliance

- believing behavior is remedied by just solving the problem

or making assumptions such as behaviors:

- are trying to upset you

- are a result of bad manners

- a demonstration that you are a bad person and not in control

- that the child must learn to behave

- must be stopped to protect the child

Acknowledging What We Find Difficult

There are some behaviors that we may find difficult such as:

- need for sameness

- inflexibility/rigidity

- meltdowns

- odd or unusual behaviors

- repetitiveness

- transitions

Learning more about why these behaviors occur and the thinking behind them can lead to a change of our viewpoint of them.

Observers must change the lens through which they view behavior. This can start with the language used to describe behavior – words like obsessive, controlling, manipulative, or deliberate place the blame on the individual and makes an assumption that it’s within that person’s power and ability to change how they act and respond. When we have a better understanding of why behavior occurs, we can shift our viewpoint and change the lens.

Changing Our Thinking

Make the paradigm shift, supported by brain science, that behavior is influenced by:

- sensory processing

- emotional regulation

- motor challenges/movement differences

- learning disabilities

- trauma

One of the hardest things for parents to do is change how they interact with their child. They may want to change their approach but fall back into ingrained habits, especially when stressed. Children may also work towards getting a certain reaction which is predictable and comforting.

Some people have conflict around how to handle and react to a child’s distressed behavior. It’s important to work as a team and have a consistent approach – this involves changing beliefs. Move away from aversive interventions such as scolding, reprimands, or punishment. Individuals have to focus on their own responses and behavior and recognize the role that they play in escalating behavior without meaning to. We need to be fluent in a collection of strategies that rapidly reduce aggression. This is done through training and practice.

Another consideration when trying to understand behavior is what level of awareness and control an individual has over their behavior.

The explanations that we have for behavior frequently implies that we believe the individual is both aware of their actions and largely in control of them; a deliberate act. This may not be the case. Think about your own everyday behavior and how many physical actions you perform when lacking awareness, control or both. Other factors that could affect which state an individual is in include their arousal state at the time and specific movement differences that they may have.

Understanding Our Role in Behavior

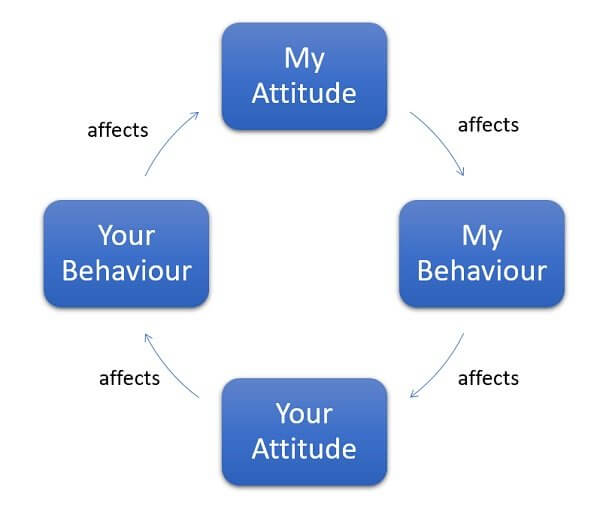

The Betari Box is a useful tool to illustrate the effects that our own behavior has on the behavior of others. It explains the cyclical nature of conflict and illustrates that a cycle will continue until we break it. It is usually easier for us to change our half of the cycle than it is for an autistic child or young person or a person with an intellectual disability to change theirs.

We are often the cause without meaning to be when behavior escalates. For example, how many times per day do we ask or tell a person we support to do or not to do something? It’s reasonable to think that each of these demands has the potential to be a point of conflict. How we respond when a person refuses could be crucial to the success of the interaction. It would be useful to think of ways we could reduce the overall number of demands placed on an individual and supporting more autonomy through the structured environment, visual schedules, and routines that are established and known. Also, identifying which demands are essential and immediate (or not) is important.

When it comes to needs and wants, how does anyone feel or react when they don’t get to have or do the things that they want to or sometimes need? When considering individuals, we should think about how developed their emotional coping skills are and how well they deal with being told ‘no’. It may not be possible or desirable to meet every need, so we need to think about the communication skills we are using when refusing someone. For example, can we show them that the preferred activity will happen afterwards by using a first/then visual support? We should also think about to our reasons when not meeting a need or want. Are we doing it for the benefit of the person, or because it’s what works best for us?

It can be hard to acknowledge that dealing with difficult behaviors can, at times, be frightening or annoying. Certain behaviors could leave us with feelings of revulsion, frustration or even anger. It’s important to recognize that all of these and more are normal and professionally acceptable ways to feel, but they need to be managed. Left unresolved these emotions can become detrimental to our wellbeing and could even affect our judgement in reflective practice, changing our lens.

Debriefing, an important part of reflective practice, is an opportunity for us to express our feelings and emotions about an incident or behavior with a colleague in a safe environment. If we don’t reflect and debrief, strong negative emotions can build towards the people we support. These negative feelings can result in something called malignant alienation. This term was first coined by Morgan in 1979. It refers to the progressive deterioration of a therapeutic relationship, when a practitioner effectively starts to dislike the individual they are supporting. It is often accompanied by a reduction in the sympathy and level of support provided. It’s the worse possible place a relationship can reach.

By being reflective, proactive, and taking preventative steps such as debriefing after an incident, we can better manage negative emotions as they come up. We’re human beings and it’s normal to get upset when things go wrong or awry.

Developing a deeper understanding of the individuals that we support through learning about their communication style, sensory needs, interests, strengths, and triggers is the cornerstone of building a positive relationship and trust. These are essential components of fostering well-being. Changing our lens will give us a different perspective of why behavior is happening and how we can best support a person who is in distress.

Editorial Policy: Autism Awareness Centre believes that education is the key to success in assisting individuals who have autism and related disorders. Autism Awareness Centre’s mission is to ensure our extensive autism resource selection features the newest titles available in North America. Note that the information contained on this web site should not be used as a substitute for medical care and advice.