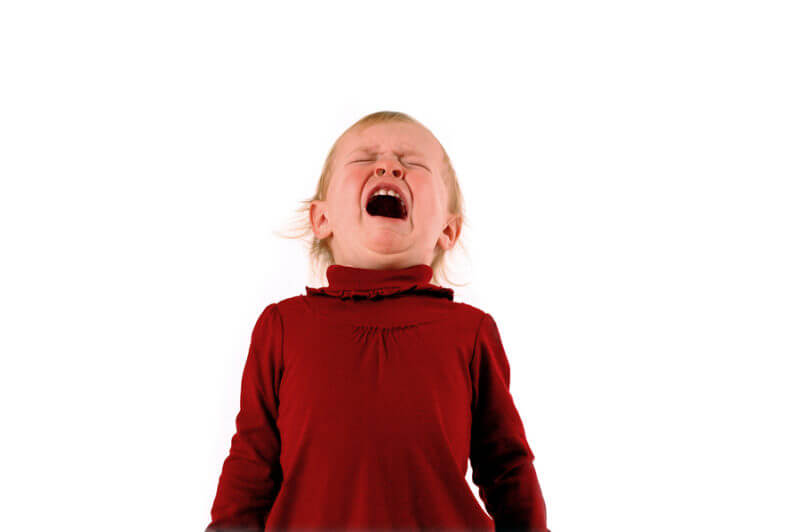

Tantrums in Autism: new study says it’s behaviour not frustration

We’ve all been there: watching as our child completely breaks into uncontrollable rage/tears in front of us. Sometimes it’s in the privacy of our own homes, but when you have a child with autism, more often than not it will be in public as well. Up until recently, there has been a common misconception that poor communication/low verbal skills in people with autism is a cause of their more frequent tantrums due to being frustrated at not being able to communicate their needs and wants. While it is likely frustrating not to be able to communicate easily, new research from Penn State College says this is not the main cause of tantrums in those with ASD.

Tantrums are rarely about communication challenges

Cheryl D. Tierney, Professor of Pediatrics, College of Medicine, Penn State Children’s Hospital says:

“There is a common pervasive misbelief that children with autism have more tantrum behaviors because they have difficulty communicating their wants and their needs to caregivers and other adults. The belief is that their inability to express themselves with speech and language is the driving force for these behaviors, and that if we can improve their speech and their language the behaviors will get better on their own. But we found that only a very tiny percentage of temper tantrums are caused by having the inability to communicate well with others or an inability to be understood by others.”

So how can we help reduce tantrums in those with autism?

Tierney states that we need to focus more on improving behavior rather than speech and langauge to reduce tantrums. Parents need to know that behavior may not improve as speech develops. They will need additional support to see improvement in behavior.

Tantrums are normal behaviour in all young children. Tantrums are about growing skills and developing independence. They happen when something blocks a child from doing something they want. The child may not yet have the skills to express strong emotions in other ways. For example, a temper tantrum may happen when a child gets frustrated because he can’t button a shirt, or a child may get upset when she is told it’s time for bed but she wants to stay up. In children with autism, this is all the more complex because of the added element of meltdowns that can look like tantrums but need an entirely different set of skills and responses. Below are three helpful hints to deal with tantrums in those with ASD.

- Determine if it’s a tantrum or a meltdown. We have written before about the difference between an autistic sensory meltdown and a tantrum, and how they each need a slightly different approach. While they might look similar on the outside, sensory meltdowns are not about frustration, and don’t have a goal. They are a response to external stimulation. Tantrums can often happen if your child is tired, hungry, or not feeling well, but they are always goal oriented, and they are always played to an audience. A meltdown will happen whether or not anyone else is around. A tantrum is designed to elicit a goal-oriented response from the person who is on the receiving end of it. Learning to distinguish between a meltdown and a tantrum is the first step to helping your child learn to manage either situation.

- If it’s a tantrum, remember that every child is different. What worked with one of your kids may not work with another. Try a variety of methods to see what works with your child.

- Remove the audience. A tantrum will often stop if the audience is removed: if the parent removes themselves, or the child is removed from the public space. If you know that your child tends to have tantrums in large groups, start with smaller gatherings until they have learned other coping mechanisms and behaviours. If you remove yourself, stay where your child can see you, but ignore them until they calm down.

- Children may also be distracted out of their tantrums. If the child seems like they are getting frustrated with an activity, suggest something that they already know how to do, and are good at. Start quietly playing with another toy, and wait for your child to come over and join you. Music or a pet can also be a great distraction.

- Change the topic. For example, if they are angry about brushing their teeth or going to bed, start talking about something fun you are going to do the next day.

- Try incentives. If they are having a meltdown over an activity that is necessary, you can try playing a short game, or bringing out a special toy with the idea that they get back to the task at hand once they have calmed down.

- Don’t forget to praise your child once the tantrum is over. It can also be good to acknowledge their feelings: ” I see you were really frustrated with not being able to get your socks on, I understand why that would make you upset. Good work on calming down. May I help you try again?” Learning to cope with challenging emotions is a very important life skill. Children should definitely be congratulated when they manage to calm themselves.

Remember tantrums are normal. It is up to us as parents and caregivers to help our children learn new skills to deal with the strong feelings they will encounter as they learn new skills. Verbal communication IS important, but learning how to deal with life’s ups and downs is not a skill you necessarily need words for.

Recommended Reading

Editorial Policy: Autism Awareness Centre believes that education is the key to success in assisting individuals who have autism and related disorders. Autism Awareness Centre’s mission is to ensure our extensive autism resource selection features the newest titles available in North America. Note that the information contained on this web site should not be used as a substitute for medical care and advice.