Tips To Teach Whole Body Listening: It’s a Tool Not a Rule

Adapted from an article by: Elizabeth Sautter, MA, CCC-SLP

Phrases like “pay attention” and “listen carefully” ring out in classrooms across the country. Moms, dads, and other caregivers can be heard saying some version of these same words to children everywhere. Paying attention and listening to others are not only considered essential for social communication, but also for learning to be part of a group and for academic success. In fact, these skills are clearly outlined in the Common Core Learning Standards that teachers use to grade their students.

Although we can easily agree that the ability to listen is important, listening involves more than “hearing” with our ears. So how is this multi-layered skill best taught? To make listening more concrete and teachable, speech pathologist Susanne Poulette Truesdale (1990) came up with a powerful, and now very popular, concept known as “whole body listening.” This innovative tool breaks down the abstract concept of listening by explaining how each body part other than the ears is involved: the brain thinking about what is being said; the eyes looking at or toward the speaker; the mouth quiet; the body facing toward the speaker; and the hands and feet quiet and kept to oneself. In a more recent article (2013) Truesdale stresses that the most critical part of whole body listening takes place in the brain. She states that “when we are asking someone to think about what we are saying, we are in essence asking for the listener’s brain to be connected and tuned-in.”

Over time, other professionals have expanded the initial whole body listening concept to include the heart as a way to encourage empathy and perspective taking. This later addition is helpful when working on social interactions and relationships in which the purpose of listening is not just to “hear” and interpret what is being said, but also to demonstrate shared involvement to make a positive impression. This expanded concept of whole body listening is woven into parts of Michelle Garcia Winner’s larger Social Thinking® methodology to teach the fundamentals of how and why we listen to figure out the “expected” behavior when around others. Similar to other Social Thinking Vocabulary that breaks down the social code, whole body listening has become a foundational concept to help make this and other abstract concepts more concrete and easier to understand, teach, and practice.

Truesdale emphasizes that whole body listening is “a tool, not a rule,” meaning that adults need to think flexibly about how best to use it. There is no “one way” to teach the whole body listening concept. The goal is to create effective approaches for those with a variety of learning styles. And most importantly, to do this in ways that respect each person’s particular needs and abilities.

Kids Do Well If They Can

When children struggle to meet classroom standards related to listening and following directions, they may be misunderstood or possibly labeled as “behavioral problems.” According to their age/stage of development, we expect children to learn how to focus, listen, and follow directions intuitively, using the “built-in” social regulation sense we assume all children possess. However, some children don’t intuitively acquire the social skills and self-regulation that we typically associate with listening. To support these children, parents and teachers need to take a step back and view the situation through a different lens.

Dr. Ross Greene, a psychologist and expert in working with kids who have challenging behaviors, suggests that we ask ourselves, “Does the child have the skills needed to perform the task?” He states it perfectly: “Kids do well if they can.” Greene believes that it is our job to figure out in which areas our children need support, understanding and/or accommodations so that they can do well. To explain listening in a way that makes sense, a host of social cognitive and sensory processing skills may first need to be concretely taught. And in some cases, children with social learning, sensory processing, attention, or other regulation challenges may not be able to perform tasks generally associated with listening, such as keeping one’s body still, making eye contact, or staying quiet.

What’s So Hard About Listening?

When we prompt children to “get out your math book,” do you get an image in your mind of what that looks like? How about “sit down”? These requests are concrete and simple to define and picture. But words like “listen” or “pay attention” are more abstract and challenging to define. What does this request really mean? How does it look in various situations and contexts? And why even care about listening? They are open for interpretation based on the person asking and the context or situation. For instance: listening during story time is different than listening on the playground or during a conversation. When a request leaves room for interpretation, the person being asked needs to be aware of and consider both the person making the request and the social rules within that context. This requires strong social attention, social awareness, and social perspective taking.

In addition, when met with a request to “listen” some adults expect children to not only listen with their ears, but to stop whatever they are doing and demonstrate that they are listening with their entire body. This adult-defined expectation may include standing completely still, similar to a soldier at attention. This is not only difficult for most children, but impossible for some. Listening with your whole body involves integrating all of the body senses (sensory processing), and combining that with executive functioning (self-control of brain and body), and perspective taking (thinking of others and what they are saying). This is not an easy task and it’s extremely important to be aware of the processing complexity involved. Many children do not fully understand what is expected of them or may not be able to meet the expected demands when it comes to listening.

Tips from Whole Body Listening Larry

Many parents, teachers, and other professionals supporting children appreciate the way that these guiding professionals have helped break down the abstract concept of listening into more manageable, concrete actions. Kristen Wilson, a former therapist at my center, Communication Works (CW) in the San Francisco Bay Area, created a story and lessons on whole body listening using a character named Whole Body Listening Larry and examples of how he struggled with paying attention. After Larry learned what was expected of him and each part of his body, he found listening much easier. He wanted to help others by sharing what he had learned.

The clients at our center could relate to Larry’s struggles. They appreciated how the story helped them learn and remember how to show that they were listening. Larry’s story also reminded kids to advocate for themselves when they were unable to focus or attend with their whole body. Kristen Wilson and I saw that Larry was an effective teaching tool and together co-authored the books Whole Body Listening Larry at Home and Whole Body Listening Larry at School (2011), which were published by Social Thinking Publishing. The books have given children a deeper understanding of what to do in various situations in which they have to self-regulate and listen, and teachers and parents have appreciated a way to talk about this concept and teach it.

A Tool, Not a Rule!

As with other tools and curricula, the abilities and developmental level of each individual must be considered before implementing whole body listening. Some of the skills used in whole body listening, such as maintaining eye contact, staying still, or remaining quiet are extremely difficult and may cause stress or simply not be possible for certain people. When this is the case it’s important that adults demonstrate awareness and understanding. Parents, teachers, therapists, and employers should make modifications and help individuals advocate for themselves in a variety of social, educational, and work-related situations.

Given the popularity of the Larry books, posters, and lessons, it is important for adults to be sure that the material is appropriate for anyone to whom it is presented. Teachers, parents, or other adults should not “enforce” this concept or any other on someone if it will cause anxiety, distress, or shame. When a child or adult is interested and capable of learning how to listen with his/her whole body it can be helpful to explore strategies and accommodations with the support team.

Whole Body Listening Strategies

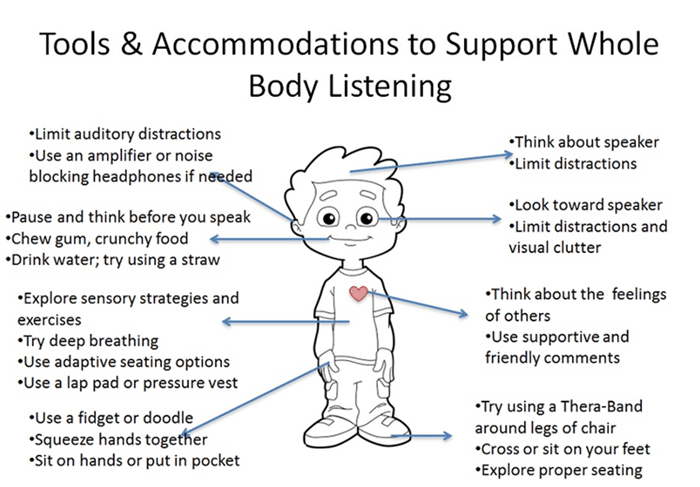

To aid in teaching whole body listening, some general strategies and accommodations follow, developed by myself and Leah Kuypers OT/R, another former therapist from CW and author of the popular curriculum, The Zones of Regulation®. Each person is different and should be assessed for individual needs and support. Also included is information to build awareness for differences that may occur, especially for those with sensory processing challenges. In these incidences modification and differential teaching should be implemented. The following visual provides a quick reference:

Ears: Limit auditory distractions. Explore the use of an amplifier (e.g., frequency modulation (FM) system) or noise blocking headphones if the child is easily distracted by background noise.

Be mindful: People who are hard of hearing or deaf can listen through ASL interpretation, lip reading, gestures, and written words or images.

Eyes: Look toward the speaker, maybe not directly but checking in for facial expressions to “read” emotions and others’ intentions. Limit distractions and visual clutter.

Be mindful: Direct eye contact can be overwhelming, intimidating, or difficult (even painful) for some. Persons can hear what is being said even if they are not looking directly at the speaker.

Mouth: Practice impulse control by pausing and thinking before speaking (brain filter). Chewing gum or crunchy food can provide sensory input that helps regulate one’s system. Drinking water, especially through a straw, can be helpful.

Be mindful: Some people need to make verbal sounds to help them process what is being said and stay calm.

Hands: Use a fidget or doodle. Squeeze hands together. Sit on hands or put them in pockets.

Be mindful: Some people move or flap their hands as a way to regulate themselves and can still listen/hear while moving their hands.

Feet: Tie a Thera-Band or deflated bicycle tubes around legs of a chair as a place to rest the feet and/or use as a fidget for restless feet. Explore proper seating for posture and comfort. Cross or sit on feet to help keep them still.

Be mindful: Some people need to move their body to stay regulated, attend, and feel comfortable. If they are moving, they can still listen and may be able to learn better.

Body: Explore sensory strategies and exercises (e.g., chair push-ups, deep breathing, etc). Consult an occupational therapist to explore adaptive seating options and use of a weighted lap pad.

Be mindful: Some people need to move their body to stay regulated, attend, and feel comfortable. If they are moving, they can still listen and may be able to learn better.

Heart: When children are developmentally and cognitively ready, help them think about why we listen to others. This includes creating rapport, a shared experience, and considering the feelings of the speaker and others and how their listening behavior might affect the thoughts of others. Practice building perspective taking and thinking about others versus themselves and their own interests during social interactions and conversation when wanting to remain part of a group and/or make a good impression. Practice using supportive and friendly comments and using the Social Fake (a Social Thinking strategy of acting interested even if you’re not) when needed. Also, help children understand that when we are around others it is socially expected that we care (pay attention to them) enough so that others feel comfortable with our presence in the group.

Be mindful: Caring about others and how our own behavior affects others in a social situation can be shown in many different ways. Don’t assume someone doesn’t care just because that person has difficulty with whole body listening. Also, it’s crucial to acknowledge and teach that some people make us feel uncomfortable. We don’t have to personally care about everyone we talk to and adults should not force caring where it doesn’t exist or if the person does not seem friendly or safe.

Brain: Teach kids about the brain and how it works. Teach short and sustained attention strategies. Practice controlling impulses. Introduce The Social Fake (Social Thinking concept) and limit distractions. Lastly, one of my most favorite tools is mindfulness, which has been proven to be a powerful tool for the brain and all other body parts. Teaching how to be aware of the present moment, on purpose, can really help with knowing when to pause and reflect before acting, and knowing how and when to use whole body listening.

Be mindful: It’s important to do a check-in before assuming that someone is not thinking about what is being said—they might show it in a way you don’t expect.

Be An Advocate

If the expectations of whole body listening prove difficult or impossible, it’s important to advocate for your child or for yourself. For example, if you or your child/student find it hard or painful to maintain eye contact, discuss this with the relevant people involved in the situation. Stating what’s real and true at the onset helps to create reasonable expectations and prevents a situation in which expectations go unmet. By modeling and teaching advocacy skills, adults help others develop the ability to speak up for themselves.

Adults can also create an environment that’s conducive to good listening by keeping expectations reasonable for the developmental and cognitive level of students. Keep these ideas in mind:

- Sitting still for long periods of time is hard for everyone, and not possible for some.

- The goal is not to create student “drones” who are taught to demonstrate whole body listening in only one specific way.

- Whole body listening should not be used to discipline children. Don’t forget that it is a teaching tool—not a rule.

- Create an environment that is conducive for listening with your whole body. Limit distractions, think about calming techniques, and be sure to support transitions and awareness for when listening with the whole body is expected.

- Help create situational awareness by talking about the hidden rules and the level of whole body listening that is expected at a given time.

Whole body listening is a useful tool that breaks down the tasks involved in listening. It has not only aided in making a complex concept clearer, but it increases awareness of expected behavior and can facilitate the teaching of self-advocacy skills. If taught, practiced and supported in a mindful manner, it can become a habit and more automatic response. However, to use this concept correctly, we must be sensitive to the unique abilities of each person. Parents, teachers, therapists, and even employers should consider the challenges that whole body listening may cause and, when needed, should adapt listening strategies to suit a person’s particular needs. When appropriate modifications are made and abilities are taken into account, whole body listening can be a powerful tool that benefits a broad and diverse range of people.

BIO

Elizabeth Sautter is the co-director/owner of Communication Works (www.cwtherapy.com). She is a licensed and certified speech-language pathologist who has been working with clients and their families since 1996. She is experienced in the areas of autism, developmental disabilities, social cognitive deficits, and challenging behaviors and since 2001, has focused most of her career on social cognitive and self-regulation intervention and training. Her latest book release is Make Social Learning Stick!(2014).

About the Books

Whole Body Listening Larry at School and Whole Body Listening Larry at Home are charming stories set in rhyme and geared to young readers in Pre-K to grade three. The authors explore how two siblings, Leah and Luka, struggle to focus their brains and bodies during the school day or at home, and the simple yet powerful teachings shared by their friend, Larry, who helps them learn more about what it means to use their whole bodies to listen and attend to others.

Editorial Policy: Autism Awareness Centre believes that education is the key to success in assisting individuals who have autism and related disorders. Autism Awareness Centre’s mission is to ensure our extensive autism resource selection features the newest titles available in North America. Note that the information contained on this web site should not be used as a substitute for medical care and advice.